Teaching LGBTQ+ Literature at UNL

In Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia, an entry about English professor Julia Penelope, who taught the nation’s first lesbian novel class (UNL’s English 310N: Twentieth Century Lesbian Novelists), indicates that the university denied her promotion to full professor, citing her lesbian research as too narrow. And teachers who have included LGBTQ+ literature in their syllabuses have at times throughout the last fifty years been challenged by students and their parents who have objected to the assigned reading. As recently as 2011, the memoir Fun Home by Alison Bechdel provoked disciplinary action within the English Department when it was assigned in a freshman composition class taught by graduate teaching assistant SJ Sindu (who has gone on to become an award-winning novelist in her own right).

The Courses

Immediately following “Proseminar in Homophile Studies,” Crompton developed “Sex Roles in Literature” as part of the English Department’s “special topics” curriculum (which were prompted by student strikes in 1970, according to the Daily Nebraskan, the campus newspaper). It eventually became a permanent addition to the English course list. While Crompton originally conceived of the course as only partially concerned with LGBTQ+ literature, those faculty who taught it in later years kept the focus on queer authors. In 1993, the subtitle “Lesbian and Gay Literature” was added to the course title (but not listed in student transcripts, out of privacy concerns). In 2002, the subtitle became the title of the course; in 2018, the title was changed to “Introduction to LGBTQ Literature” to better reflect the diversity of the body of work studied. An advanced level of the course was also introduced that year: “LGBTQ Literature and Film.”

Julia Penelope introduced “Twentieth Century Lesbian Novelists” in 1977, which was another first for the English Department; it was the first course devoted to lesbian fiction to ever be offered by a US university. In an article in the Daily Nebraskan, Penelope (who went by the name “Julia Stanley” at the time) noted that there were no problems with the approval process for the course. Penelope also noted that she discouraged men from taking the course. “Lesbianism has nothing to do with their lives,” she said.

Proseminar in Homophile Studies

— by Lexus Root

Alongside James Cole (the director of the training program for clinical psychologists) and Louis Martin (a psychiatrist), Crompton was an instructor for the class. There were also provisions afforded to have thirteen invited lecturers attend the class, which included scholars from other institutions and a former police officer. With the experience and training of those involved, they attempted to develop a cross-disciplinary analysis of homosexuality, which included the legal, anthropological, political, psychological, and theological dimensions of homosexuality. For this last dimension—the theological—Crompton had spent the better part of his 1970 summer in Berkeley studying; it is fitting, then, that it was the very first section included in the syllabus’s reading list. The literary works of gay authors were also studied, such as those of James Baldwin (Another Country), Mart Crowley (The Boys in the Band), and John Rechy (The City of Night).

Crompton, a respected scholar on the critic George Bernard Shaw (his book on Shaw won a 1969 award by Phi Beta Kappa for its contributions to literary theory), was deeply involved in the gay rights movement, leading the Lincoln–Omaha Council on Religion and the Homosexual, and overseeing the religious committee at the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO). A month after a task force at the National Institute of Mental Health called for increased academic attention to homosexuality, he submitted his course syllabus to university officials. Approval by university personnel came quickly and without controversy, but the board of regents soon became involved.

The course was never offered again. In the middle of a letter dated December 4, 1970, to someone at NACHO named Land, Crompton instructed him: “Don’t tell this to any reporters”. He indicated that due to the election of “two new anti-homophile” regents, he began to expect “that they will may suppress the course,” and that Carpenter was committed to eliminating the course with a new bill to transfer it again elsewhere. Even though the university’s administration had shown a “cheering liberalism,” he was concerned that they would not defend future iterations of the class as vigorously as they had before Carpenter. His initial inclination to write “will,” his worry of Carpenter’s legal maneuvering, his cynicism regarding the university, and his insistence on not having the information told to reporters, all suggest Crompton feared that continuing to offer the course would put in danger any future classes of homosexuality in Nebraska. He seems to have preferred the cancellation of this single course to the suppression—or if Carpenter were to get his way, the elimination—of a wider study of sexuality. Despite these worries and his frustration, Crompton’s letter was not entirely negative: Student organizations devoted to homosexual advocacy was comforting, and he predicted they “will do more than a thousand courses.”

The Faculty

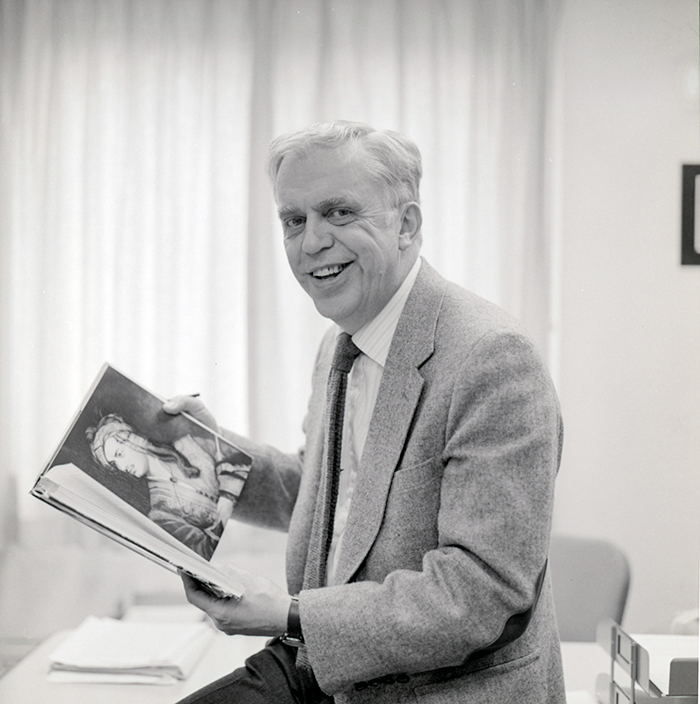

Louis Crompton

Louis Crompton, photographed in 1985.

Whatever the vocabulary, two elements are present–the sexual fact and the possibility of love and devotion. For many centuries in Europe, homosexuality was conceived principally as certain sexual acts. This was because it was viewed theologically and in the light of the legal system this theology spawned–that is, as a sin and a capital crime. But we must not be complicit in this dehumanization

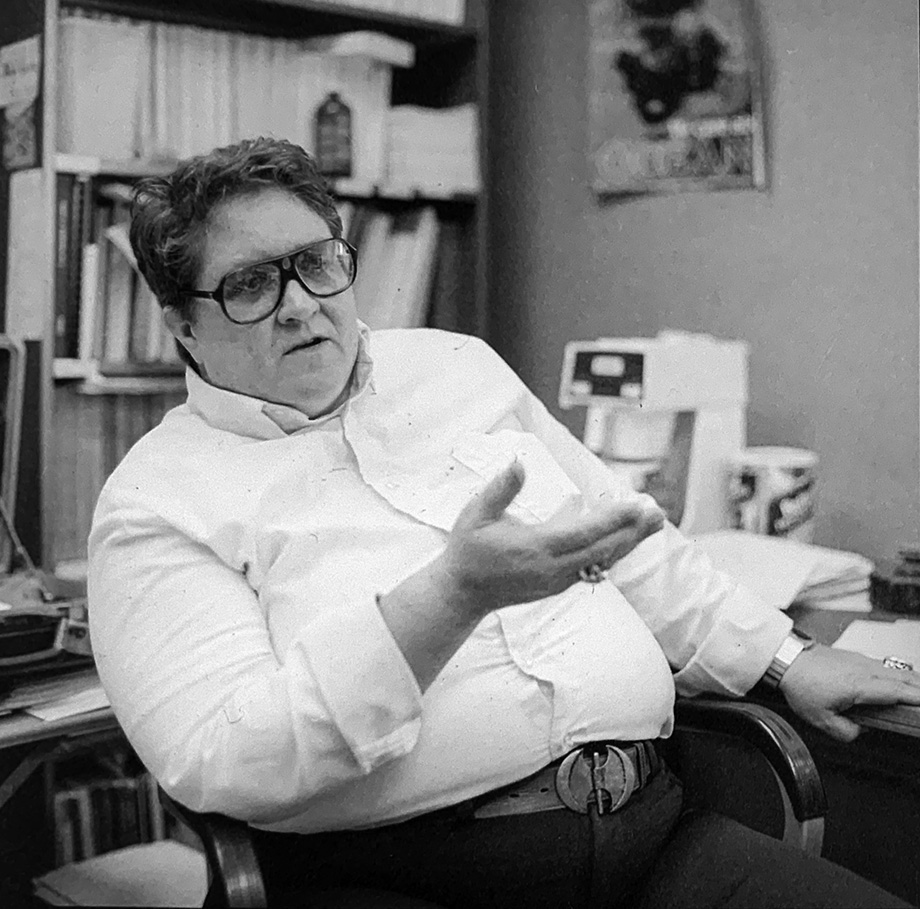

George Wolf

George Wolf joined the English Department in 1966, and was mentored by Crompton. He taught “Sex Roles in Literature” and facilitated the addition of the subtitle “Gay and Lesbian Literature” to the course in 1993. He also regularly taught “Gay and Lesbian Drama.” He campaigned actively for partner benefits for LGBTQ+ faculty and staff for many years, and he received awards for his teaching, for his defense of academic freedom, and for his contributions to the LGBTQ+ community.

“A fundamental education has to take us from the provincial place we all start from, whether its geographical provincialism or ideological provincialism, and then we enter a world that is supposed to tell us the world is much more complex than we imagined.”

Julia Penelope

Julia Penelope, a linguist who also published under the name of Julia Stanley, taught in the UNL English Department for eleven years; much of her scholarship addressed the patriarchal influence on language.

Little that is heretical or even unconventional goes on in WS [Women’s Studies] classes. Dangerous questions go un-asked. WS has devolved into the sort of mindless nattering our most hostile male colleagues predicted it would. What if WS abandoned the genteel effeminacy of its present curriculum and really threatened the foundations of our social structure, called into question every value, and asked questions that are not only unspeakable but unthinkable in any other context? What if we dared to be dangerous?

In only her second year as a professor of English at UNL, Julia Penelope offered “Twentieth Century Lesbian Novelists” in 1978, the first time such a course was taught at a university in the US. The fact that the course failed to make news proved newsworthy: the Lincoln Journal ran the headline, “Lesbian novelists class causes little turmoil.” While Penelope herself refused to address the course for the article (“I don’t think it will be adequately presented by the media”), the English Department chair at the time, Charles Mignon, spoke in support of the class. According to the Journal article: “Although he received flak from a few faculty members within the department, Mignon said he received no negative response from students or persons outside the university.”

Penelope did speak, however, to the Daily Nebraskan, the campus newspaper. “We live in a society where men like Dr. David Reuben in Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask) can say lesbians just don’t exist,” Penelope said. “Who knows how many millions of people have read that one vagina plus one vagina equals zero and believe it? People don’t want to listen to lesbians since [lesbians] are a living testimony that it is a lie that men are essential to women.”

According to her official obituary, written by Sarah Valentine, her executor, Penelope “took joy from knowing that the governor of Nebraska wanted the word Lesbian to stop appearing on the front pages of the Lincoln newspapers in the late 70s, early 80s.”

At the time, Penelope went by the name Julia Stanley, but she would drop her father’s last name in 1980, in the spirit of her research; among her books was Speaking Freely: Unlearning the Lies of the Father’s Tongue, on the patriarchal foundations of language. An acclaimed linguist, she wrote about the influence of gender and sexuality in language, and in slang especially. In 1970, she published “Homosexual Slang” in the journal American Speech.

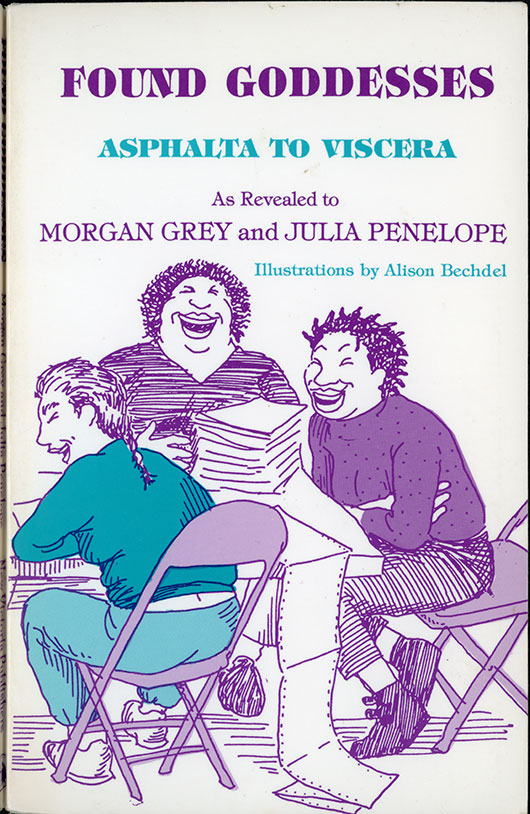

The book Found Goddesses (1988), co-written by Penelope and Morgan Grey, is a playful approach to this study, with illustrations by Alison Bechdel, who was already well-known within the queer community for her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. (Bechdel would win wide acclaim for her graphic memoir Fun Home upon its publication in 2006; the book would be adapted into a Tony-winning musical.)

On the back of Found Goddesses, a blurb by poet Joy Harjo, who would many years later serve as US Poet Laureate, opens with “What do you get when you mix the jaded and irrepressible humor of a wild lesbian linguist and the magical sensibilities of a radical lesbian witch who are making it in a strange world called Lincoln, Nebraska?”

In her eleven years with the university, Penelope served as a pivot point for lesbian activism and culture, bringing Lincoln into a national conversation on gender and sexuality. Penelope formed the Lincoln Legion of Lesbians in 1976 (homosexuality was illegal in the state of Nebraska until 1978), and she facilitated the relocation of Sinister Wisdom, the national lesbian arts journal, to Lincoln for several issues. She was one of the founders of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, currently housed in Park Slope, Brooklyn. And she brought to campus prominent lesbian writers and scholars, such as Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich.

painfully honed and polished,

no word lies cool on your tongue

bent on restoring meaning to

our lesbian names, in quiet fury

weaving the chronicle so violently torn.

As a “lesbian separatist,” Penelope was criticized for discouraging men from enrolling in her lesbian literature class and from attending events organized for women. She was also criticized for applying separatist ideology to other queer identities, and even within the lesbian community itself. This criticism led her to eventually abandon writing altogether, citing “lesbian infighting,” according to an entry about Penelope in Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia. The entry also notes that she left academia after she was denied promotion to full professor at UNL, her lesbian research dismissed as too narrow in scope.

In the words of Sarah Lucia Hoagland, Penelope’s co-editor on the book For Lesbians Only, “Julia Penelope was a master strategist, fomenting lesbian culture, a trickster, a raging lesbian, and brilliant.”

Barbara DiBernard

Shortly after Barbara DiBernard joined the English Department in 1978 as a James Joyce scholar, she was introduced to Women’s Studies, a field that was entirely new to her and new to academia in general. She committed to teaching women’s literature courses as part of the emerging Women’s and Gender Studies program (which she would direct from 1992-97), and published articles on diversity in the classroom, and on teaching literature by women with disabilities. She facilitated the retitling of “Sex Roles in Literature” to “Lesbian and Gay Literature,” established the “Intro to LGBTQ Studies” course, and she carried Julia Penelope’s “20th Century Lesbian Novelists” class forward into the 21st century. She also offered graduate seminars on the topic, which included a course titled “Walker (Alice), Sarton, and Lorde.”

Photo by Francis Gardler, Lincoln Journal Star

This portrait of DiBernard with Judith Wilson ran in the Lincoln Journal Star in 2015 on the occassion of the Supreme Court’s legalizing of gay marriage; they were the first same-sex couple in Lancaster County to receive a marriage license.

Excerpt from an interview with DiBernard with the Daily Nebraskan in 2000:

Q: What misrepresentations about women’s studies do you frequently come across?

A: One is that women’s studies is political, and other courses are not. Other courses are considered truth, while women’s studies and ethnic studies are considered political. They are considered advocacy. They are considered not “the real stuff.”

My belief that I think is the belief of other people in women’s studies is that all education is political. If you teach American history, what you put in the class, and what you leave out is considered political.

I don’t think it’s bad to say that all education is political. People think political is a bad word. But I think education is political in a sense that it has value structure, and it has a philosophy.

Another perception is that women’s studies is all about lesbians. Lesbians are women, lesbians write good literature, lesbians contribute to history and every aspect of life.

Women’s studies stands for inclusiveness racially, in terms of sexuality, in terms of disability, in terms of age and in terms of class.

Amelia María de la Luz Montes

Amelia María de la Luz Montes is an Americanist (Chicanx/Latinx) LGBTQ scholar and creative writer, currently at work on a memoir, La Llorona on the Danube: A Mexi-Yugo Memoir. She has taught LGBTQ literature courses at UNL since joining the English Department in 2000.

By night, she became known in small intimate circles as the Mariachi Dyke. In San Luis Potosí, Mexico, where she was born, Antonia had learned to play the vihuela. She could sing too. By the time she was in fourth grade, she led her Tío Tan’s band, singing at quinceñeras, bodas, and under balconies at six in the morning. The morning serenatas were what she loved most. The serenatas helped Antonia, at fourteen, realize she loved women. She’d be singing “Bésame morenita” or “Ven, novia Rosita, ven” outside a woman’s window, when whoever was behind the door or curtain would finally reveal herself and nod to her. Antonia would nod back, or if the woman was attractive to her, she would bow.

Melissa Homestead

Melissa Homestead has been on the English Department faculty since 2005. She has taught courses on LGBTQ authors of the nineteenth century, and she directs the Cather Project and serves as Associate Editor of The Complete Letters of Willa Cather: A Digital Edition. She was hired at UNL based on her research into Edith Lewis, Willa Cather’s partner of nearly 40 years. In 2021, she published The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather & Edith Lewis with Oxford University Press, the culmination of 18 years of research.

In the epilogue to The Only Wonderful Things, Homestead writes:

Timothy Schaffert

Timothy Schaffert began teaching LGBTQ literature at UNL in 2007. He is the co-editor, with SJ Sindu, of Zero Street, the LGBTQ+ fiction series of the University of Nebraska Press. He is the director and curator of “50 Years of LGBTQ Studies at UNL,” an ongoing festival of events and projects commemorating UNL’s LGBTQ+ history. His novel, The Perfume Thief, was a #1 bestseller on Amazon’s list of LGBTQ+ Historical Fiction.

Here, a woman could put on a three-piece suit and a gentlemanly monocle without anyone calling the law. And these mischief-makers dared to think this could be the way of things from now on, this manner of living the way they wanted to live, of loving who they loved. Instead of changing themselves to fit in, they decided to change the world. Instead of becoming more like the people they weren’t, the people they weren’t might feel compelled to become more like them.

Stacey Waite

Stacey Waite is a professor in the Composition and Rhetoric program of the English Department, and the author of Teaching Queer: Radical Possibilities for Writing and Knowing. Her scholarship includes the articles “Queer Literacies Survival Guide” and “The Unavailable Means of Persuasion: A Queer Ethos for Feminist Writers and Teachers.” She is also a poet (on the page and on the stage, leading several slam poetry events), and the author of the poetry collection Butch Geography, among others.

Brian Nelson, I will not leave this tire swing.

I will not put down this GI Joe. I will not stop

kissing your sister in the sandbox. I will not stop

spitting in the woods. Brian Nelson, your hands are

little machetes, your voice a small army of soldiers.

Brian Nelson, did you know that female hyenas

mount the males? Did you know you cannot tell

the gender of a loon without cutting it open?

Did you know some cultures worship androgyny?

They call us all-knowers. And I know you,

Brian Nelson. I know how hard it is

to be a boy. I know how hard it is

to protect masculinity, its skin as thin

and fragile as the holy playground air.

Gabrielle Owen

Gabrielle Owen’s interest in children’s literature has informed and shaped her research on queer adolescence, which is the subject of her book A Queer History of Adolescence: Developmental Pasts, Relational Futures (University of Georgia Press, 2020). She teaches queer theory in the English Department, and incorporates its tenets into her classes on young adult literature.

Excerpt from the introduction to A Queer History of Adolescence: Developmental Pasts, Relational Futures:

James Lowell Brunton

James Lowell Brunton is a writer, artist, and scholar of film and media studies, critical theory, and LGBT studies, and he serves as the coordinator of Film Studies in the Department of English. His work includes Opera On TV, an experimental writing collection, and he co-edited, with UNL alum Kristi Carter, TransNarratives: Scholarly and Creative Works on Transgender Experience. He is at work on a graphic novel/memoir called From the Neck Up.

Excerpt from From the Neck Up: