Early Years

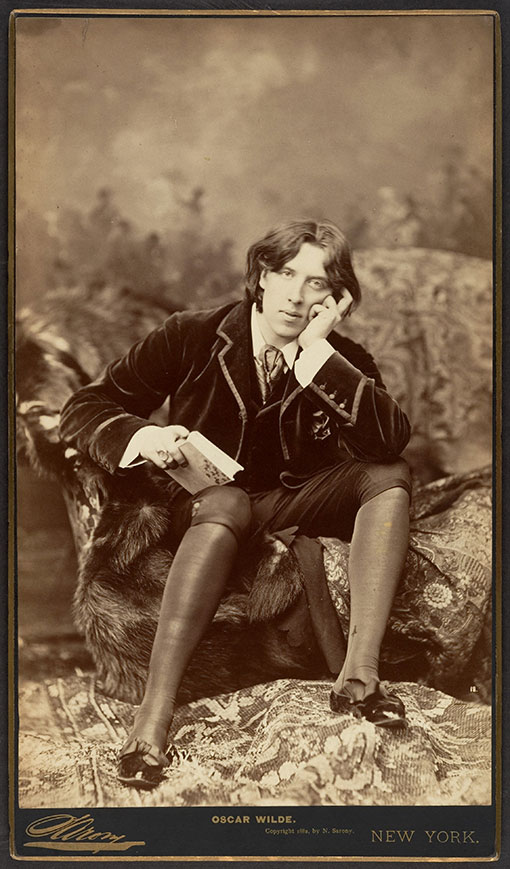

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde photographed in 1882 by N. Sarony, New York. Met Museum, Gilman Collection

Oscar Wilde, photographed in 1882 by N. Sarony in New York near the beginning of his American tour. Photo from the British Library, Shelfmark Add MS 81783 A.

While in Lincoln, Wilde read some of the English professor’s poetry, and offered his assessment. Woodberry described this moment in a letter to a friend: “’Poetry,’ he had said, “should be neither intellectual nor emotional’ – and so I pleased only in describing external beauty though he had a true ear for music and style of single lines. He praised what I thought commonplace – he did not mind what I thought imagination.”

Willa Cather & Louise Pound

“It is manifestly unfair that ‘feminine friendships’ should be unnatural, I agree with Miss De Pue that far.”

Much has been made of the observation above, a line from a letter Willa Cather wrote college classmate Louise Pound in 1892. Together, Cather and Pound were English majors at the University of Nebraska, where they were involved with a student literary magazine called The Lasso, among other collegiate projects. And based on letters that Cather wrote Pound (and wrote others about Pound), Cather was clearly infatuated with her. The letters also indicate they spent much time together, and while Pound’s biographers insist she didn’t return Cather’s affection, and their friendship would become strained and end within a few years, their relationship did have some intensity of feeling that would one day provide Cather’s biographers insight into her sexuality.

Louise Pound (left) and Willa Cather. Image from History Nebraska RG 1951.

Cather’s humble beginnings as a rural Nebraska girl are perhaps made even more interesting when we consider her rejection of gender expectations and conventions; she often signed her letters as William Cather in her teens, and wore her hair in a short, boyish cut. And while it’s been widely reported that she wore trousers, there’s no historical evidence to support such a claim. A local man who knew her in her childhood wrote that she had “masculine habits and dress” but there are no eye-witness accounts of her ever wearing pants. She was part of a child’s acting troupe for which she played the male roles, and so would wear pants accordingly for the performances; but wearing trousers as part of her daily get-up might have been a bit too bold even for Cather.

In a photo of Cather and Pound, circa 1892, Cather (on the right, in the dark hat) is wearing a tailored suit, but it’s not in a masculine style – those flared sleeves are definitely feminine. The hat, however, might be said to have a masculine shape, but throughout her life, Cather wore hats of a wide variety of styles, as did many women. So what’s most telling about Cather’s sexuality is not the cut of her suit; it’s her affection for her classmate.

After graduating, Pound went on to become an award-winning athlete and pioneer of the linguistic study of American English. She eventually returned to the university as a professor, where she taught for fifty years. Cather, in her many years after graduating from the University of Nebraska in 1895, became one of the most acclaimed writers of the first half of the 20th century, often ranked alongside Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald as the most influential of American novelists. Even Hemingway and Fitzgerald themselves acknowledged her influence: in an infamous letter, Hemingway criticized her Pulitzer-Prize-winning novel, One of Ours, mocking it as a cliché-driven portrait of war, in statements that sound like a jealous snit; Fitzgerald wrote her a fan letter as he was composing The Great Gatsby.

A formative article, which then led to a book, on Cather’s sexuality and gender was “‘The Thing Not Named’: Willa Cather as a Lesbian Writer,” by Sharon O’Brien, published in 1984. In this article, she speaks to the challenges of identifying people as lesbian in a time when such self-identification was rare, especially among public figures. She asserts that the line about unnatural feminine friendships in Cather’s college letter to Pound is characteristic of lesbian sensibility.

Though there’s no historical record of Cather ever identifying as lesbian herself, her life partner of 40 years was Edith Lewis, an editor and writer. The leading scholar on Cather’s relationship with Lewis is a professor in the UNL English Department. Dr. Melissa Homestead’s book, The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather and Edith Lewis, was published by Oxford University Press in 2021, and is the culmination of 18 years of research.

Willa Cather, photographed when she was a student in the early 1890s. Image from History Nebraska, RG1951.

While UNL is home to the Willa Cather Archive and the Cather Project, both of which include scholarship that considers Cather’s sexuality, the university’s English Department had a history of suppressing lesbian scholarship in the 20th century. This brings us to another letter, one written nearly a century after Cather’s love letter to Pound.

Virginia Faulkner and Bernice Slote are credited with advancing Cather scholarship in the 1950s and 1960s, saving Cather from slipping into obscurity after her death. Faulkner was editor of the University of Nebraska Press and Slote was an English professor and an editor of the literary journal, Prairie Schooner.

In a letter dated March 14, 1980, Faulkner writes frankly about the rigor of these efforts. This letter has been referenced in a few books on Cather, such as in Willa Cather: Double Lives by Hermione Lee and Willa Cather and the Politics of Criticism by Joan Acocella, but in neither case is Faulkner’s relationship with Slote mentioned. [The letter is archived in the Virginia Faulkner papers in the Archives & Special Collections of University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.]

The letter, on UNL letterhead, is addressed to Helen Southwick, Cather’s niece. Faulkner starts the letter by referencing a play about Cather, “a documentary drama,” that has “a lesbian angle,” which Southwick had expressed concerns about. Faulkner says that “all the discussion about [Cather’s] homosexuality” has been going on for 20 years, and she references having heard rumor that “a woman scholar is working on a ‘psychosexual’ study about which I know only that she wasn’t planning to send it to Nebraska because of our ‘conservative’ treatment of Willa Cather.” This is possibly in reference to O’Brien’s research, or to that of lesbian scholar Doris Grumbach, who was also working on a biography of Cather at the time.

Melvin Van den Bark

Excerpt from an article by Jamison Wyatt

At Iowa he began an extensive study of Nebraska pioneer English, which became his master’s thesis, and he began works of fiction, such as “Two Women and Hog-back Ridge.” Published in the literary journal The Midland, “Two Women” was reprinted in the anthology The Best Short Stories of 1924.

Melvin Van den Bark. Image from Mari Sandoz Collection.

“Two Women” is remarkable to me for two reasons. One: it is the only extant work of Van’s fiction. Two: it is an unmistakable autobiographical account of Van’s rural teaching experience and is a clear expression of his queerness. In the story, Van cloaked himself as Mary, a young woman with big eyes, sallow skin, and short black hair (this is an identical description to Van’s World War I draft card). Mary, born in Omaha, belonged to a family of blue-collar laborers and desired a life away from factory drudgery. Instead, she attended high school, took the normal-training course, and traveled deep into the Sandhills to teach at Midvale, Nebraska, a rural community in southern Brown County. For Mary, teaching was not necessarily a profound calling but a means of escape. Once in the Sandhills, however, Mary, like Van, discovered a certain poetry in the “sea of yellow, green, lavender folds:”

Though Van never published any other fiction, and his papers are presumably lost, his legacy lives on through his The American Thesaurus of Slang (1942)—which contains a lengthy section of queer terminology and is still referenced by contemporary lexicographers—and through the works of his students, especially Mari Sandoz.

“I stopped when a man waved a paper bag (lunch of some sort I’ve since decided). Anyway he wanted to go to a cheap hotel for a night’s lodging or to the depot. I offered to take him to the depot.”

In Van’s inebriated state, he likely saw two opportunities: a chance for another drink from the paper bag and a chance for a late-night tryst with a stranger. The restrooms of both bus and train stations were common places where queer men could cruise and have sex. Van and the stranger, however, never reached the depot.

“At the next corner he wanted ‘to take a dump’ in a hurry, so I drove out tenth a ways. Then during that activity, a police car drove up. The rest of the night and next day (yesterday) I spent locked up in a cell that was as barren as any Valin writes about”

“Valin” could possibly be a poor, phonetically spelled variation of Paul Verlaine (1844–1896), a French poet who was arrested and imprisoned after he injured his male lover.

Sandoz was outraged but saw the ordeal as an inevitable witch hunt. Responding to Van’s letter, Sandoz wrote, “I’ve frankly said that your name was on the list with the police ever since the [Lowry] Wimberly affair, your name and others.” Unlike the Wimberly scandal, however, Van’s arrest and resignation were publicly kept quiet. In Sexual Inversion, Havelock Ellis presciently wrote that individuals connected with public schools “appear to view homosexuality with too much disgust to care to pay any careful attention to it. What knowledge they possess they keep to themselves, for it is considered to be in the interests of public schools that these things should be hushed up.” Perhaps Van’s “immorality” was simply too publicly shocking. Humiliated, he borrowed money for gas and drove away from Lincoln never to return.

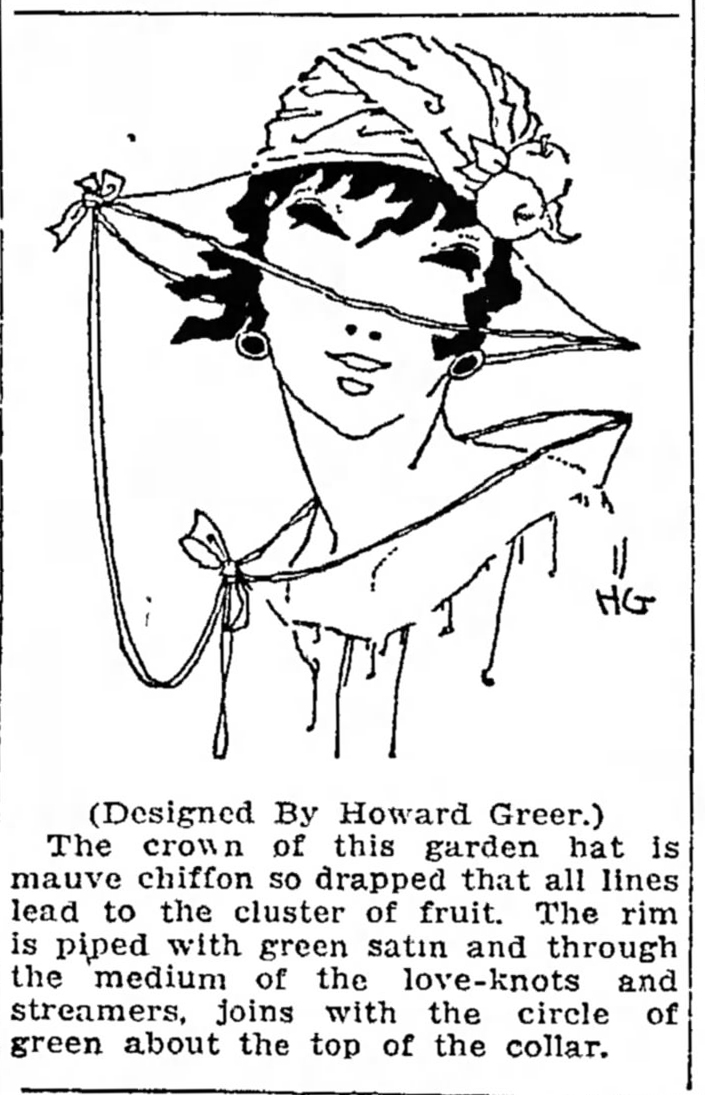

Howard Greer

Howard Greer enrolled in the University of Nebraska to become a writer, but after graduation in 1916, and service in the first World War, he embarked on a career as a costume designer for the New York stage. (Greer dressed The Greenwich Village Follies of 1922, which included a ballet based on Oscar Wilde’s fairy tale, “The Nightingale and the Rose.”) He found his way to Hollywood, where he would go on to design costumes for Katherine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby, and for Ingrid Bergman in Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound, among many other cinema stars in classic films. He also famously hosted parties for the queer elite, according to the book Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians (by Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons): “He hired local female impersonators from ‘a queer nightclub that ha[d] just started.’” His elaborate staircase served as a runway for the city’s drag queens impersonating movie stars.

In 1951, Greer published his memoir, Designing Male: A Nebraska farm boy’s adventures in Hollywood and with the International Set, in which he wrote of his intentions of going to the university to become a writer:

It took a terrific amount of persuasion, but I convinced Mother that I’d derive greater scholastic benefit from the larger and more sophisticated University of Nebraska, and there I enrolled for my sophomore year. The net result was that I floundered in an even more confusing milieu of student activities and social snobbery and, for the first time, the idea of complete escape assailed me. I’d read so much about Greenwich Village and its artists that could have walked through it blindfolded, and not lose my way. Here I would find my niche and, at the moment it didn’t seem particularly important whether the niche was musician’s, artist’s, writer’s, dancer’s or actor’s. A career as a writer shouldn’t be difficult I assured myself. After all, I’d not only edited the senior yearbook, but I’d written an interview with Billie Burke on one of her appearances in Lincoln, and the local paper had published it. Furthermore, I’d sent a short story, with sketches, to Frank Crowninshield of Vanity Fair, and received in return a check for twenty-five dollars for “the idea suggested by the story and the drawings”.

Or I could climb the ladder of fame on which artists perch. I’d always drawn pictures, and people were most flattering over my copies of Harrison Fisher’s ladies from the covers of the Saturday Evening Post. I might even crash the advertising game, and give Coles Phillips a run for his money. And there were always the magazine serials, and I might make May Wilson Preston look to her laurels. More than anything else I liked to sketch women, with or without clothes, and I drew the feet first and then worked upward. If anyone had looked into his crystal ball at that time and told me that someday I might become a dressmaker, I’d have spit in his eye.

With all Mother’s passion for my attaining a college diploma, I wonder now that she ever allowed me to quit school for something so vague as a dream. Her first-born’s overwhelming determination and obstinacy worked on her resistance like the old Chinese water torture but she gave in, at long last and with obvious misgivings, to my assault upon New York. The one obstacle was the financial backing necessary for such a venture. When Mother agreed to mortgage the old homestead I closed my textbooks and walked out of classrooms forever.