Opportunity & Opposition

A Century of Women’s Athletics at the University of NebraskaEarly Rise and Fall of Women's Intercollegiate Athletics

From Drilling to Dribbling

In 1883 women at the University of Nebraska petitioned the Board of Regents for “an amount of gymnastic training that will be an equivalent for the military drill that is provided for gentlemen.” The Board of Regents appropriated $25 to outfit a room for women’s calisthenics in 1884. Within a decade the University had established a program offering women regular exercise and athletic instruction.

Basketball soon became a popular sport for women on campus. Invented by James Naismith in 1891, basketball was a relatively new game when Women’s Gymnasium Director Anne Barr introduced it to classes in 1896. That year the first interclass games were played. In 1897 Louise Pound joined as team captain, and the players took on their first outside opponents, a team from Council Bluffs, Iowa.

Varsity Basketball

Women’s varsity basketball team, 1902-1903. Top row: Edith Craig, Pearl Archibald, manager Louise Pound, Zora Shields. Bottom row: Cora Scott, Elva Sly, Minnie Jansa, Alice Towne.

Competition expanded and included an annual tournament with other local teams beginning in 1900. The top team was awarded a Russian samovar donated by Anne Barr. Winning the tournament for three consecutive years, the University of Nebraska women became the trophy’s permanent owners.

In November 1901 the team played its first intercollegiate match and defeated the University of Missouri. The 1902 University yearbook, The Sombrero, highlighted the team’s successful record. Anticipating a promising future, the yearbook reported efforts to bolster intercollegiate athletics.

Only six years later, in April 1908, the Board of Regents voted to end intercollegiate athletics for women.

The Final Season

As women’s varsity teams sought opportunities for intercollegiate competition, opposition emerged. Dean of Women Edna Barkley was a prominent opponent.

Barkley fought to prevent the women’s basketball team from playing home and away games against the University of Minnesota in 1908. At that time, women’s athletics were governed by the Athletic Board. The Board overruled the Dean’s objections, and the women played both games.

After a tough 22–28 loss in overtime at home, the women spent weeks drilling and tightening up their skills under the leadership of team manager Louise Pound and trainer Ina Gittings. The team traveled to Minneapolis, Minnesota, for what would be its final intercollegiate game, winning 9–3 on Saturday, April 4, 1908.

“On hearing of negotiations which are being carried on between Minnesota and Nebraska relative to a girls’ intercollegiate basketball game, a complaint was filed with the Athletic Board asking that this proposed game be cancelled.”

Women's Intercollegiate Athletics Ends

In April 1908 the University Senate made significant changes to the Athletic Board. The changes included removing women’s sports from the Athletic Board’s oversight and revoking women’s ability to vote in Athletic Board elections. This left women’s athletics without a governing body or a system of support.

On April 7 the Board of Regents assigned their Property Committee the task of considering Dean of Women Edna Barkley’s concerns about women’s intercollegiate athletics. Newspaper coverage and Alice Towne Deweese’s memoir suggest Barkley may have cited the physical and emotional toll of higher-level competition as well as the distraction from classwork generated by big games.

During the Regents’ meeting April 24, 1908, members of the Property Committee reported their recommendation, “that the young ladies of the university student body shall not engage in interstate games and contests.” The Regents accepted and adopted the recommendation, eliminating women’s varsity intercollegiate athletics for nearly six decades.

Interclass Athletics, 1909-1924

Women's Athletic Association

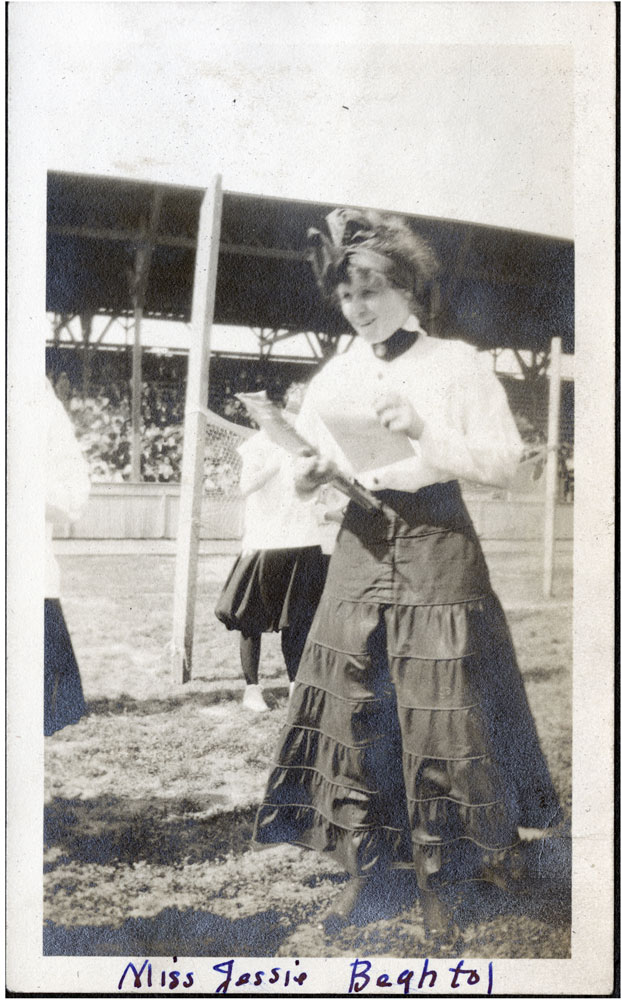

In March 1917 students founded the Women’s Athletic Association (WAA). Aided by physical education instructors Dorothy Baldwin and Jessie Beghtol Lee, they established the WAA to organize and regulate athletic competitions for women and provide a system of awards for successful competitors. Competitions provided an opportunity for women to discover and demonstrate their capabilities. Reporting the results of the three WAA basketball tournaments held in 1918, Jessie Beghtol Lee wrote:

“Time was when the college girl was supposed to do one of two things – she could bone hard and get herself a P.B.K. or she could dance and wield a feather fan at proms. But no girl was ever supposed to do both. This was the happy day when all ladies were supposed to be afraid of mice and faint at the sight of blood. But owing to a number of things – largely the passing of time and the unceasing demand made by women for recognition in every phase of life—this has all been changed. Women can make munitions, they can run factories, they can plow farms — and they not only can do it but they are doing it every day of their lives . . . And not only can the college woman work to point and purpose, but she can play, keeping the rules, and obey the dictates of the referee and umpire quite as well as anyone . . . These tournaments enabled one hundred and fifty girls to compete in actual playing for prizes, gave healthful and pleasant recreation for many more, and proved conclusively that girls’ athletics, when managed by girls of character and discretion, can be made one of the most important influences of college life.”

The 1923 WAA constitution outlined a scaled system for awarding points, which rewarded both participation and accomplishments.

Athletes received points for membership on class and intramural teams and for individual sports. The number of points awarded ranged from 100 points for membership on primary class teams to 5 points for third place in a track event.

Mabel Lee's Leadership, 1924-1952

A Sport for Every Girl and For Every Girl a Sport

As Director of the Women’s Physical Education Department from 1924 to 1952, Mabel Lee influenced women’s athletics at the University of Nebraska for nearly thirty years.

Lee opposed women’s intercollegiate athletics. Instead, she favored intramural sports and play for play’s sake. Lee felt intramural sports expanded opportunities to all women, regardless of their athletic skill. Intercollegiate athletics, on the other hand, would limit participation to highly-skilled athletes.

She also believed women should be safeguarded from physical and emotional challenges associated with intense competition. She worried students would be exploited if their athletic contests became spectator sports generating ticket revenue and pointed to men’s intercollegiate athletics as an example of the danger.

A leader in the field of physical education, Lee became the first woman president of the American Physical Education Association in 1931. She rose to prominence in national and regional organizations and frequently wrote and gave speeches related to women’s physical education and sports.

In 1948 Lee won the Luther Halsey Gulick Award for long and distinguished service, the American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation’s highest honor. The association honored her again by establishing the Mabel Lee Award in 1976 to recognize outstanding young professionals.

Argument’s Against Women’s Competitive Athletics

Mabel Lee included a section titled “Competition” in her 1937 book, The Conduct of Physical Education: Its Organization and Administration for Girls and Women. Arguing against women’s interscholastic athletic competition, Lee focused on women’s basketball as an example to illustrate competition’s drawbacks. According to Lee:

It produces both physical & emotional strain which is harmful to the girl.

The temptation to participate during the menstrual period is a serious hazard to future health.

It is more frequently accompanied by rowdyism than by cultural influences, which hinders the best personality development of all who are involved.

It leads to neglect of studies on the part of players and to neglect of other important extracurricular activities and teaching on the part of the coach and sponsors.

It brings undesirable publicity to girls.

It leads to a distorted conception of the values of athletics.

Whatever values might exist in such procedure can be gained only at too great a sacrifice of other values.

A long program of intense competition seriously curtails the girls’ freedom to pursue a normal life and brings many unwholesome experiences as happens to boys and men who are varsity players involved in commercialized athletics.

Such a program breeds the “coach” type of instructor as opposed to the “educator” type and the “professional” type of player as opposed to the “amateur” type.

Pressure Against Funding Women’s Varsity Sports

“No school–and especially not Nebraska–has a sufficient staff and equipment to turn out varsity teams for various sports of the year, and at the same time to carry out a correct program of physical education for the remaining University women.”

As early as 1926, inadequate funding to support both women’s varsity sports and physical education reinforced opposition against women’s intercollegiate athletics. Opponents claimed “the few” skilled enough to play varsity sports would benefit at the expense of “the many” physical education majors if the Women’s Physical Education Department spent general funds on intercollegiate teams. In contrast, men’s physical education and men’s athletics were considered distinct from one another and received separate funding. Military drill provided basic physical education for men, and men were provided opportuntities for both intramural and intercollegiate sports.

Women’s Athletic Associations members selling concessions to raise funds, 1927.

The Women’s Athletic Association raised money selling concessions at men’s football and basketball games. Following principles adopted by the Athletic Conference of American College Women in 1924, the WAA opposed women’s intercollegiate athletics and did not provide funding to support varsity teams. Instead, WAA funds supported annual charity projects and sponsored lectures, alumni luncheons, banquets, and parties. The WAA purchased equipment used by both the intramural program and the Physical Education Department. From 1934-1952, the WAA leased land north of Bethany, where they maintained a cabin for group outings.

WAA Emphasizes Recreation

WAA Brochure, 1929

The WAA brochure from 1929 reveals Mabel Lee’s influence on the organization. With a dedication to Lee and forward written by her, the brochure persuades students to try intramural sports: “The worse you are, the better we like it, because the more progress you’ll make and progress is what we crave. Besides, Intramurals are not out to make records or record-breakers. They are here for the sole purpose of making you happy, and the way they do it will make you marvel.”

WAA members hiking, 1925

In summarizing the organization’s history, the 1931–1932 WAA President’s report described the WAA’s early years as: “Much big varsity activity midst cheers and earning great sweaters and numerals and sporting them to the world seemed to be the platform of the WAA.” According to the report, by 1928 the WAA aimed to, “if possible grow away from this old idea of playing to win; of getting out to get practices to pile up points toward a big letter to wear on a sweater; to reduce the desire for individual awards; and to increase participation, to make it possible for every girl in the University to participate in some sport activity.”

Extramurals & the Return of Intercollegiate Athletics

Forming Extramural Teams

In 1965 the Women’s Athletic Association developed an extramural sports program to compete against teams from other colleges. WAA board members hoped the program would provide opportunities for “well-skilled girls.”

A field hockey team played their first extramural match October 30, 1965, after holding six practices. The extramural season included volleyball games with Nebraska Wesleyan and an additional field hockey game held at Doane College in Crete, Nebraska.

Nebraska Women’s Intercollegiate Sports Council (NWISC)

On April 22, 1967, representatives from Nebraska colleges and universities met to discuss setting up a league for women’s intercollegiate sports and formed the Nebraska Women’s Intercollegiate Sports Council.

In the 1969–1970 season the NWISC held its first recognized women’s intercollegiate state tournaments in volleyball, basketball, softball, and swimming.

The University of Nebraska won the NWISC State Volleyball Tournament in 1970. Eleven teams competed in the double elimination tournament. Team members (left to right): front row, Kathy Drewes, Kathy Crewdson, Dee Fentimen; back row, Peg Tilgner, Pam Miller, Debbie Knerr, Jan Cheney, Karen Ostrander, and Coach Connie Ludwig. These team members, along with Elise Mahoney and Linda Perry, were invited to the second DGWS National Intercollegiate Volleyball Tournament.

With a 7–0 record heading in to the NWISC State Softball Tournament, the University of Nebraska team took the title in 1971. They defeated Kearney State 6 to 3 in the championship game.

WAA Focuses on Intercollegiate Athletics, 1971-1975

After the Department of Recreation began overseeing the University’s intramural sports program, the WAA focused on intercollegiate sports. The WAA board and coaches from the Department of Physical Education managed the program’s budget and organized teams and, in 1973, created a handbook for the women’s intercollegiate athletics program.

On August 26, 1975, after administration of women’s intercollegiate athletics had shifted to the Athletic Department, the WAA decided to dispose of its assets and dissolve. The Association disbanded during the 1975–1976 academic year.

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972

On June 23, 1972, President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law. Title IX prohibits sex-based discrimination and requires education programs or activities receiving federal financial assistance to comply with Title IX regulations. If an educational institution does not comply with the regulations, it may no longer receive federal financial assistance.

Title IX’s application to intercollegiate athletics led to increased funding for women’s varsity teams and athletic scholarships for women.

In addition, as the University moved toward compliance, the Athletic Department took on general supervision of women’s athletics in 1974 and designated Gail Whitaker as Assistant Athletic Director. In July 1975 the University hired Aleen Swofford as the first full-time Women’s Athletic Director. After nearly seventy years, women’s athletics were once again part of the Athletic Department.

Funding for Women’s Teams

When the WAA contract for concessions ended in 1947, the Athletic Department agreed to provide the WAA $1,500 each year in place of the concession revenue. This yearly payment formed the core of the women’s intercollegiate athletics budget in the early 1970s.

Physical Education faculty members coached the women’s teams, and the department provided facilities and some equipment. The responsibility strained the department’s resources. The budget was too tight to cover many basics like athletic shoes, warmup uniforms, publicity, coaches’ salaries, and travel costs.

During a WAA board meeting in May 1973, members even considered holding a bake sell at the local shopping mall to raise funds for women’s teams.

Although Title IX broadly offers protections against discrimination, its application to athletics became a major focus of attention after its passage. Many worried revenue-producing sports like men’s basketball and football would be gutted if colleges were required to provide women’s athletic’s equal funding. Groups, including the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the American Football Coaches Association, lobbied to exempt revenue-producing sports or to entirely prohibit the application of Title IX to athletics.

In 1975 Title IX federal regulations for athletics were issued and schools were required to comply within three years. The Report of the Chancellor’s Title IX Review Committee on Athletics presented to Chancellor Roy A. Young, December 5, 1979, showed increased funding for women’s athletics as the University worked toward compliance.

Athletic Scholarships

The University of Nebraska did not award athletic scholarships to women until after Title IX. National and local organizationsn overseeing women’s athletics opposed women’s athletic scholarships. Leaders believed athletic scholarships professionalized college sports and overemphasized student athletes’ identities as athletes rather than students.

NWISC Scholarship Prohibitions

On April 23, 1972, the Nebraska Women’s Intercollegiate Sports Council (NWISC) passed a motion barring membership to colleges and universities that awarded athletic scholarships to women or recruited women to play sports. Schools with these practices were also prohibited from playing in NWISC state tournaments. The ban on scholarships and recruiting reflected standards set by the Division of Girls and Women’s Sports (DGWS) of the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation and the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW).

AIAW Ban on Women’s Athletic Scholarships Ends

In January 1973 plaintiffs from Marymount College and Broward Community College in Florida filed a lawsuit challenging the AIAW ban on women’s athletic scholarships. Part of the plaintiffs’ argument relied on Title IX’s prohibition discrimination on the basis of sex. Responding to the lawsuit, the AIAW changed its policy but not its philosophy. Announcing the end of the women’s athletic scholarship ban, the association clarified their position: “We wish it to be understood that this practice is not recommended but it is now permitted.”

The University of Nebraska first awarded women’s athletic scholarships in 1975. In a Title IX Self-Evaluation dated March 24, 1975, the Athletic Department reported 164 men received full athletic scholarships, and 86 received partial athletic scholarships with a total $539,000 awarded to men. No women received full athletic scholarships, while 56 received partial scholarships. In total, women’s athletic scholarships amounted to $37,448.

In a University-wide Title IX Self-Evaluation from 1976, the self-evaluation committee acknowledged the gap in scholarship awards and recommended women athletes receive roughly proportional awards. The Chancellor’s Title IX Review Committee on Athletics reported women were awarded 26 full athletic scholarships and 36 partial scholarships for the 1979-1980 academic year.

Title IX’s Legacy

After Title IX, the University of Nebraska women’s intercollegiate athletic program expanded, with increased funding and institutional support. However, the shift toward equitable opportunity for women athletes was neither instantaneous nor total. More than a century after women at the University of Nebraska petitioned for equitable physical training, collegiate athletes press on toward equitable opportunities.

Bibliography

Board of Intercollegiate Athletics, RG 39-04-00. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Centralized Academic Files, Chancellor Records, RG-05-01-01. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. Prohibition of Sex Discrimination., 1975. Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare on S. 2106 to Amend Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. United States Senate, Ninety-Fourth Congress, First Session, 1975.

Correspondence, Women’s Athletics Records, RG-39-20-04. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Durward B. Varner, Correspondence, President Records, RG-02-03-01. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Edwards, A. “Why Sport? The Development of Sport as a Policy Issue in Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972.” Journal of Policy History, 22:3, 300-336, 2010.

Faculty, Physical Education for Women Records, RG-23-18-02. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Hoepner, Barbara J., Ed. Women’s Athletics: Coping with Controversy. American Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation Division for Girls’ and Women’s Sports, 1974.

Husker Happenings, Women’s Athletics Records, RG-39-20-01. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

James H. Zumberge, Outgoing Correspondence, Chancellor Records. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Lee, Mabel. “The Case For and Against Intercollegiate Athletics for Women and the Situation Since 1923.” The Research Quarterly of the American Physical Education Society, 2:2, 93-127, 1931.

Lee, Mabel. The Conduct of Physical Education; Its Organization and Administration for Girls and Women. A. S. Barnes and Company, 1937.

Lee, Mabel. Memories Beyond Bloomers, 1924-1954. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, 1978.

Lee, Mabel. Memories of a Bloomer Girl, 1894-1924. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, 1977.

Memoirs and Theses, Physical Education for Women Records, RG-23-18-07. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Miller, Jana. “Women’s Athletics On Move – Director.” The Lincoln Star, 3 August 1975. p. 2C.

Minutes and Agendas, Board of Regents Records, RG-01-01-02. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Nebraska Women’s Intercollegiate Sports Council (NWISC), Women’s Athletics Records, RG-39-20-03. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Newsletter, Physical Education for Women Records, RG-23-18-05. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

Photographs and Slides, Physical Education for Women Records, RG-23-18-11. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

“Policies on Women Athletes Change.” Journal of Health, Physical Education, Recreation, 44:7, 51-54, 1973. Region VI, Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), Women’s Athletics Records, RG-39-20-02. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Reports and General Files, Board of Regents Records, RG-01-01-01. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Robert D. Scott, English Papers, RG-12-10-10. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Samuel Avery, Correspondence, Chancellor Records, RG-05-10-01. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Samuel Avery, University Correspondence, Chancellor Records, RG-05-10-03. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Samuel Avery, Subject Correspondence, Chancellor Records, RG-05-10-04. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Samuels, Jocelyn and Galles, Kristen. “In Defense of Title IX: Why Current Policies Are Required to Ensure Equality of Opportunity.” 14 Marquette Sports Law Review 11, 2003.

Scrapbooks, Physical Education for Women Records, RG-23-18-09. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Staurowsky, Ellen J. “A Radical Proposal: Title IX Has No Place in College Sport Pay-For-Play Discussions.” 22 Marquette Sports Law Review 575, 2012.

Stewart, Pamela. “Creating Staunch Hearted, Bright-Eyed Sportswomen: The Montana Legacy of Athlete and Educator Ina E. Gittings.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 66, no. 1: 3–17, 2016.

Subject Files, Physical Education for Women Records, RG-23-18-03. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Title IX Coordinator, Chancellor Records, RG-05-00-01. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

University Photos, University Communications Records, RG-42-12-02 and RG-42-12-03. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Verbrugge, Martha H. Active Bodies: A History of Women’s Physical Education in Twentieth-Century America. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Ware, Susan. Game, Set, Match Billie Jean King and the Revolution in Women’s Sports. University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Women’s Athletic Association, Physical Education for Women Records, RG-23-18-13. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

Exhibit created by Traci Robison, Outreach Archivist & Assistant Professor of Practice, 2023.