H Alice Howell

A Woman's Journey Through the Early 20th Century

A Force for Change

During the Victorian Era and through the Edwardian age, men dominated theatre and the dramatic arts. This was no different in Lincoln, where men operated the two major theatres and directed their companies. However, in 1900, Harriet Alice Howell, or simply Alice Howell, would change theatre both at the University of Nebraska and in Lincoln.

Howell was also active in social movements and volunteered in World War I. She continued to change the lives of her students, advancing her own studies by traveling abroad, and volunteered again in World War II. She cemented her influence at the university and continues to stand out as a prominent figure in UNL’s history today.

“Nothing can disturb the calm poise of my regnant soul.”

Alice Howell was born to a Canadian family who settled near Omaha. At a young age, she was known to entertain guests and put on little shows for her family. Howell went on to high school, received education and degrees from two different universities, and started her masters at the University of Nebraska. While she was finishing her studies in Lincoln, she created the Dramatic Club in 1900.

The Dramatic Club

The Dramatic Club put on small productions and met in the old University Hall. At this time, a new building was to be built on campus, but for “religious and social” purposes, as well as housing a small theatre. The Temple building was completed in 1908 and it was here Alice Howell had her office, among the Y.W.C.A offices, alumni association, and other social groups in Lincoln. Over the course of the university’s history and the dramatic club turning into a university department, the Temple Building became the center for university theatre, as it remains today.

The Dramatic Club went through different phases in the early 1900s, as the group became more established and affiliated with the university. They were briefly the Temple Stock Company and then the University Players, when they finally became a school department. Over the years, they struggled with budgeting and were in debt many times. At one point, the university made the decision to shut down the School of Fine Art, where the Dramatics Department was held, and moved all of the visual and performing arts to the School of Arts and Sciences.

Making an Impact

As shows were being produced at the new Temple, Howell campaigned for women’s suffrage around Nebraska. She was vocal on women’s issues throughout her life and was president of the College Equal Suffrage League as well as other university affiliated women’s clubs.

Meanwhile, the powers in Europe became divided and war spread. Howell took a leave of absence as soon as the United States joined the Triple Entente and became a canteen worker in France. She was able to resume her position at the University after the war.

In the decades that followed, unrest grew in Europe and a new political party saw its rise to power in Germany. The Third Riech invaded Poland, causing Europe to engage in war yet again. As France fell under German control, Alice Howell resigned from the dramatic department for good. She turned to help with the war, just as she did 20 years prior. Howell became the secretary for the British War Relief Society in Lincoln, and helped with fundraisers and clothing drives that were donated to aid the war effort. As the United States entered the war, she continued community aid.

Unfortunately, Alice Howell never saw the end of the Second World War. She passed away in July of 1944, suffering from a stroke after a short illness only a few weeks earlier. A service was held for Howell in Lincoln before she was buried in Wyoming.

A Closer Look

1874

Alice Howell was born in Weeping Water, NE. She was the youngest of six children, with roughly eleven years between her and her eldest brother Edward. She was described as “flamboyant” and was known for being dramatic and theatrical.

1890

Howell graduated from Central High School in Omaha and started her college education at the University of Washington in Seattle. She received a bachelors degree in pedagogy, which is a term for the method and practice of teaching.

1895

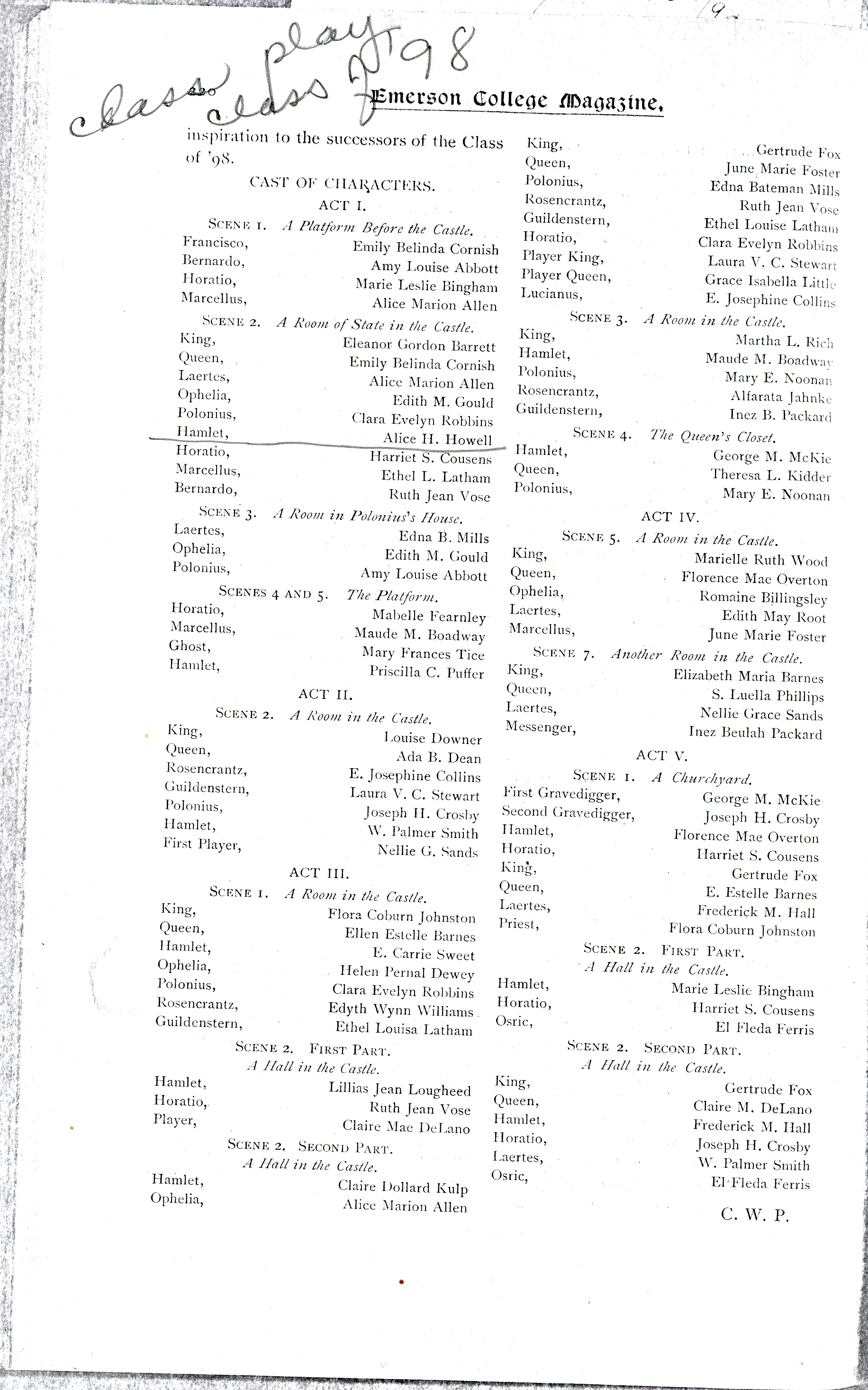

After graduating from the University of Washington, Howell made her way to the other side of the country to study at Emerson College of Oratory, now simply Emerson College, in Boston. There, she studied dramatics and elocution, or the skills needed to speak clearly. She was also a part of the class play in 1898, in which she played Hamlet.

Emerson College Catalogue

Page from Emerson College catalogue in which Alice Howell participated in the class play and played Hamlet in one of the acts.

1900

Alice Howell moved back to Nebraska and received a masters from the University of Nebraska. The university did not have a school of dramatics at this point, nor did it have a dramatic club, and Howell made it her mission to change that. She also became the professor of elocution.

“Special interest was felt in the appearance of Miss H. Alice Howell, head of the department of elocution. The new hall is rather large for a woman’s voice, yet Miss Howell was heard without the least difficulty in all her gradations of tone. She gave the readings from prose and poetry announced in the program and also a number of shorter selections as encores. Her voice is of an agreeable quality and is capable of considerable dramatic intensity.”

1906

Construction on the Temple Building began, but with some controversy. It was partially funded by oil tycoon heir John D. Rockefeller Jr., which caused backlash within the community. Many did not want to be associated with “dirty oil money” as the Rockefeller family was criticized for engaging in unethical and exploitative practices.

The Temple was originally for “religious and social purposes” with offices, a cafeteria, a stage, and other amenities. Howell had her office here for a time and shared the space with the other groups that pertained to the university. The building functioned as the predecessor to the Nebraska Union.

1911

The University Players

Photograph of the University Players in the 1913 edition of the Cornhusker, with Alice Howell in the middle of the front row.

1914

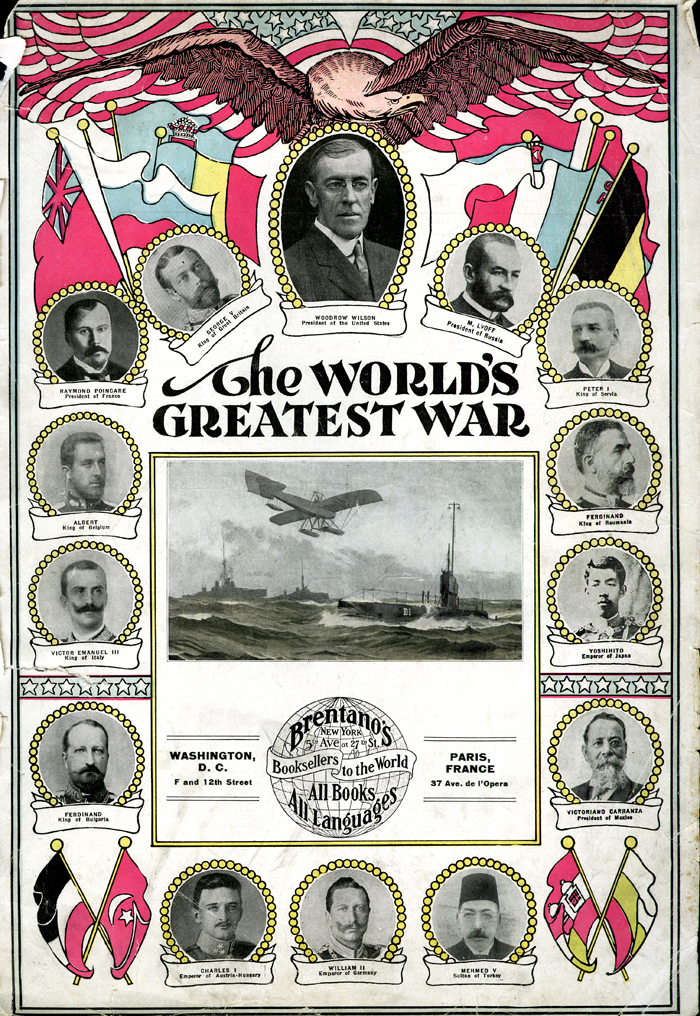

The heir of Austro-Hungary Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist. Austro-Hungary gave Serbia conditions to follow, and after their refusal to comply, Austro-Hungary declared war on Serbia July 28, 1914.

As war broke out, the powers of Europe divided into alliances. The Triple Entente, consisted of Britain, France, Russia, Japan, Italy, and many of the Bulkan States. The Central Alliance included the German Empire, The Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. Fronts opened up throughout Europe, the Middle East, and into Africa.

World War I

Three images taken by J. Patras. Image 1 shows soldiers in Oulches, France. Image 2 shows soldiers in gas masks disinfecting an area for mustard gas. Image 3 is the American cemetery in Verdun.

1917

Despite anti-war protests, the United States joined the Triple Entente and declared war on Germany. The U.S tried to stay out of the conflict for as long as possible, but the German Empire used unrestricted U-boats to attack US merchant ships, with the hope of starving out Britain. These attacks included the sinking of British liner the Lusitania, an event in which 128 American civilians were killed. Not only did the Germans target American lives, the U.K also intercepted the Zimmerman Telegram. This was a correspondence from the German Foreign Minister asking Mexico to join the war with the Central Powers, in exchange for help in taking back Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico from the U.S.

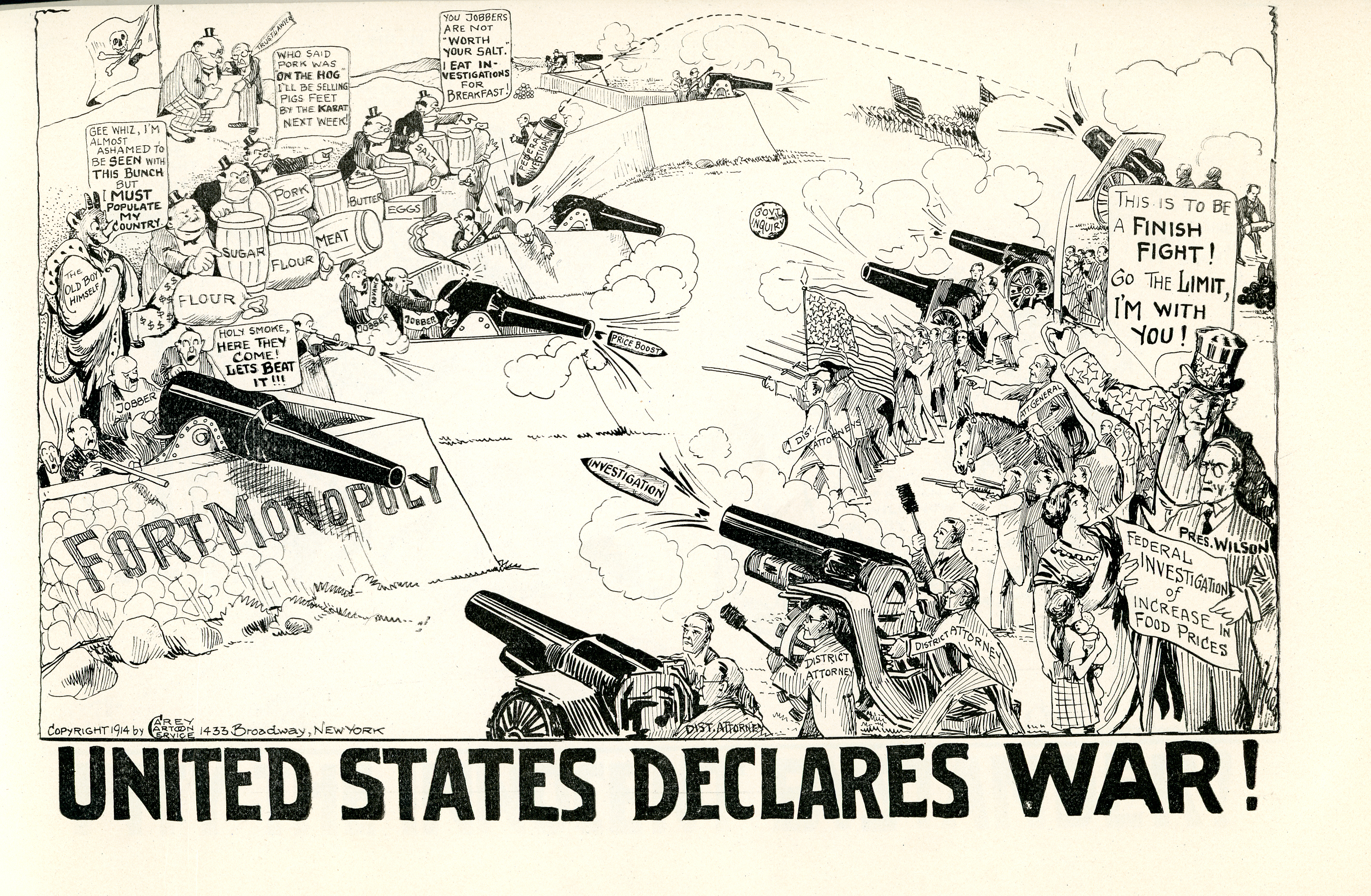

Political Cartoon

World War I cartoon made in 1914, three years before the United States entered the war, imagining what it would be if the US did enter the war.

1918

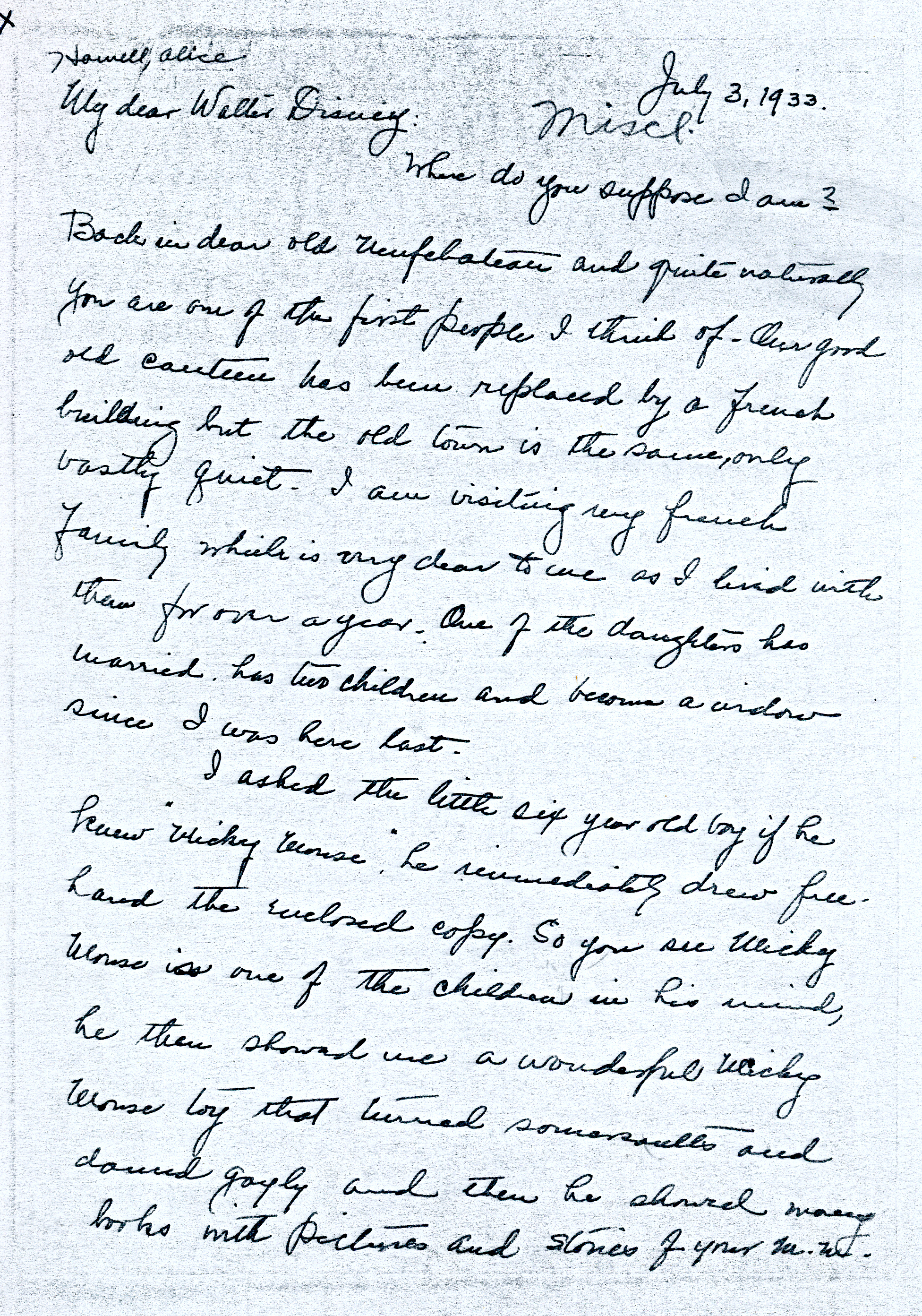

Alice Howell signed up to work at canteens for the American Red Cross. She was stationed at a hospital in Neufchâteau, France. There, she was given the degree of D.M, Donut Maker, and she distributed hundreds of doughnuts a day. She also made deliveries and pickups to warehouses and other canteens throughout the area with her driver, a young man known to draw caricatures in his off hours named Walter Disney.

Howell was also a librarian in the research library attached to the hospital, in which she helped doctors find books. Since she was in close proximity to the front, she was able to meet with her old friend from Lincoln, General John Pershing. Another time, she was arrested for being mistaken as a German spy because she accidentally walked into a restricted area.

“That was the highest point in my life. I don’t suppose I can ever hope to attain such heights again. If there ever is another war I certainly will enlist, I hope there won’t be another.”

Alice Howell and Walt Disney Correspondence

A letter from Alice Howell to Walt Disney during their 13 year correspondence between 1931 up until Howell’s passing in 1944. This letter is on her return to Neufchâteau. For a closer look at this letter, click on the button below.

Alice in France

Newspaper article on the return of Miss Howell and her time in France as an American Red Cross canteen worker.

Western Front of World War One

Map of the western front in World War One, along the French and German border, spreading up into Belgium as well. Miss Howell was at Neufchâteau.

1918-1920

Before Howell returned to Lincoln, a virus started to spread across the globe. The influenza pandemic could have been blamed on the globalization of hundreds of thousands of people due to the war. Regardless, it spread to infect one-third of the world’s population, and is considered one of the deadliest pandemics in modern history. Back in Nebraska, the University closed for three weeks, with all activities suspended. They encouraged students to report illness and quarantine if possible. The university discouraged large events, however, many still occurred on campus. The health department encouraged gargling, sleeping, and eating “wholesome food”. This event parallels the COVID-19 pandemic precautions.

“The epidemic of Spanish influenza which has visited army camps and cities all over the country, and which is piling up a huge death toll wherever it makes its attacks, has reached Lincoln and now has made its appearance in the University. Every effort will be made to check the epidemic before it gets a foothold on the campus. In spite of precautions now being taken eleven cases are already known to be among students. One student was sent to the hospital Tuesday and several others are confined to their homes.”

Since the war effort was helped by thousands of women in the United States, Alice Howell included, the suffrage movement came to a head when the pressure increased to allow women to vote. Some western states had already granted women the right to vote, and the first bill was introduced to Congress in 1878. The amendment was not ratified for another forty-two years. It should be noted that this mainly applied to white women, as “laws excluding many Native Americans from voting unless they relinquished their tribal affiliations persisted well into the twentieth century, and in that same century, many people of Chinese and Japanese ancestry were denied the right to become citizens and exercise voting rights. Black Americans’ voting rights have been formally barred and legally undermined since the conclusion of Reconstruction—by Jim Crow laws, white terrorism, and the systematic closing of polling places in precincts with a majority of Black voters. Latinx voters also have also been affected by the scarcity of polling places, as well as by racial rhetorical containment and barriers to accumulating political capital in the border states whose boundaries were imposed on their forebears.” (Anderson 226)

League of Women Voters

A 1945 Newspaper article on the anniversary of the League of Women Voters. Alice Howell was heavily involved in the Nebraska League’s creation and activism twenty-five years prior.

1929

The roaring twenties saw economic and social excess. Prohibition created speakeasies and an era of celebration. It all came to a halt when the stock market crashed, and despite government optimism, it gave way to the worst economic depression of the modern age. Trading records were broken and the mass selling and turnover of shares overwhelmed the market. Not only was the econmic crisis dire in the United states, but the whole world was feeling its effects.

1933

“If one is pursuing an art she must be prepared to receive criticism, but it seems to me that she should not thereby lose her vision of what she is trying to do because of petty comments. I consider Mrs. Robey’s criticisms most petty, in fact, I find that she did not attend the play that she criticized the most.”

With the nation still engulfed in the Great Depression, The University of Nebraska decided to close the School of Fine Art, and move dramatics to the School of Arts and Sciences. The University Players were $6,000 in debt ($124,243.85 in 2021) from the building of the Studio Theatre in Temple, as well as their finances going under the management of the university’s finance secretary.

It was also during this time that Alice Howell received criticism from the Women’s Temperance Union, asking for the performances to be censored from swearing and drinking. In response, Howell called those comments “petty”.

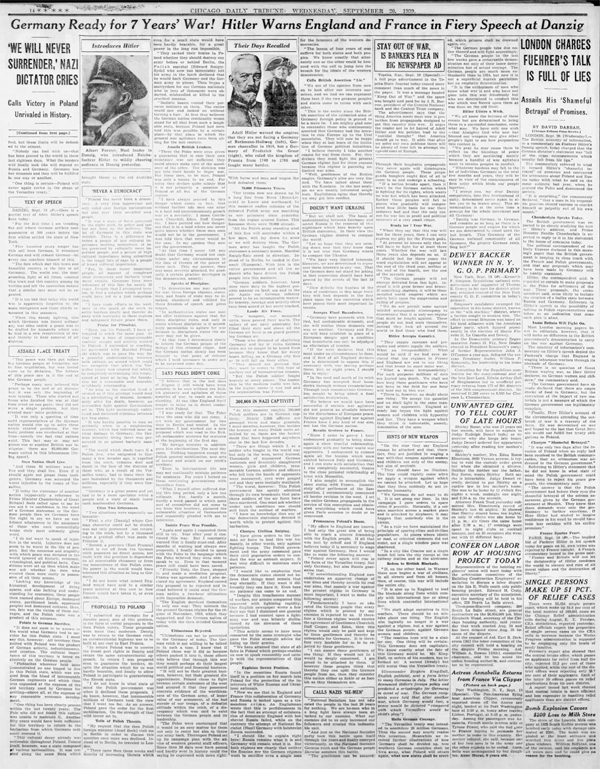

1939

Germany had been struggling since the war twenty years before, and they needed a leader to get the country out of the economic crisis. That leader came in the form of a man who was able to convince the public that specific people, most notably the Jewish community, were to blame. Nazism began its rise, using herd mentality to its advantage. Eventually, Hitler had started his dictatorship as the Third Reich, and invaded Poland as well as France, which started the Second World War.

The powers in Europe were once again split into sides, with the U.S joining the Allies after the attacks on Pearl Harbor. This war was not only bloody on the fronts, but gave way to the mass genocide and extinction of several targeted groups of people, claiming upwards to 12 million lives.

As bombs rained down on London during the Blitz, and Britain continued to fight against facism, Alice Howell took leave of absence, and eventually, resigned from the university. She had several disagreements with Chancellor Boucher on the state of the dramatics department. Sources claimed Boucher was known for being rude to Howell and commenting that she was too old to continue.

After leaving, Miss Howell focused her efforts on helping out with the war, as she said she would six years prior. She became the secretary to the British War Relief society in Lincoln, raising funds and supplies to send across the pond.

“Alice was extremely bitter toward Chancellor Boucher. I think she could have accepted retirement in good grace, if it had been presented to her with some delicacy. But my understanding is that Boucher was extremely crude and brutal. Simply said she was old. And told her to get out.”

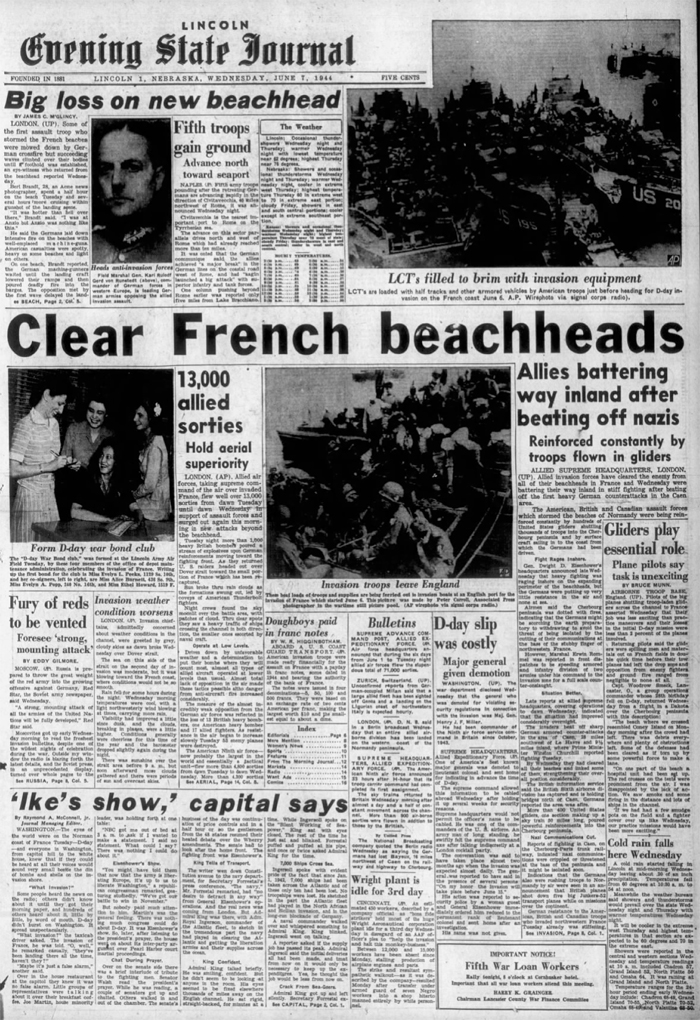

June 1944

As the war continue to rage on, the need to invade Nazi-occupied France became more apparent to the Allies. They had called it Operation Neptune, known now to the world as D-Day. It was the largest sea invasion at the time as the Allies tried to capture towns in Normandy. They divided the coast up into five sections; Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. The battle ended with thousands of casualties, but a new hope for the Allies as they were able to keep moving inland. This marked a turning point in the war in favor of the Allied Powers.

July 1944

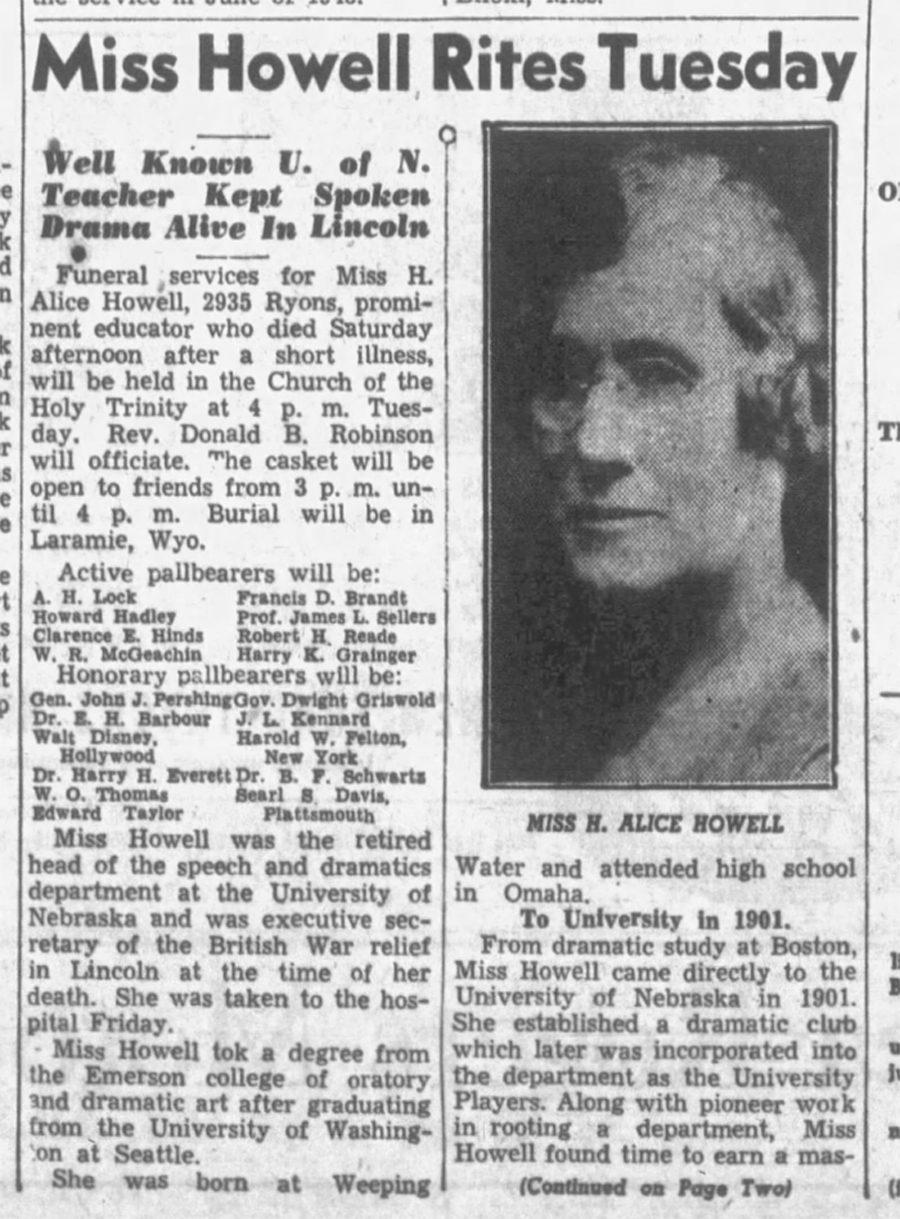

Not seeing the end of the war, H Alice Howell passed away at the age of 70 in Lincoln. She had suffered from a stroke and a short illness. A memorial service was held for friends and students of new and old to pay their final respects before Howell was moved and buried at a cemetery in Laramie, Wyoming, where most of her family moved in previous years.

“Miss Howell displays a personality so gracious and wholesome that she wins and holds the closest attention and heartiest sympathy of her hearers.”

Miss H Alice Howell’s Passing

Newspaper article on Miss Howell’s passing as well as a look into her life.

“She was known to both students and faculty as “The Queen” and that’s the way she ran the department. You understand, of course that we did not call her this to her face; but the term was an affectionate one and her queenly and autocratic behavior was recognized and accepted by everyone. To sum it up, she kept on top of everything and everyone in the department, including all student majors, and usually had the final word in all departmental administrative decisions.”

A Woman’s Legacy

Miss H Alice Howell

lived a plentiful life, enriching those around her with wisdom as well as bettering herself through experiences. She gave her life to her work and her students, believing that there was no greater joy than that. Much like her role model, Jeanne D’Arc, Howell influenced several generations of students as well as being a bright light to those who knew her. She was resilient and powerful in an age when women were not given much of a chance to excel.

A more extensive look into University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Johnny Carson School of Theatre and Film and its own in depth history can be found on the university’s libraries and archives and special collections website. It covers every show in all entities, from the start of the Dramatic Club, all the way to present day. The collection consists of photos, programs, publicity, and other publications.

“…I was privileged to play the part of Jeanne d’Arc. For years I have admired her courage, her wonderful faith and hope until she has become my ideal of womanhood…I was permitted to go to her land, the land of Jeanne D’arc.”

University Players’ Jeanne D’Arc

The University Players’ production of Jeanne D’Arc, with Miss Howell as Jeanne, in the center on a white horse. Produced in 1916.

Sources

Alan Neilson, Theater Papers, (MS-0064). Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

“Alice Howell, Teacher, Dies: Active in Work of War Agencies.” Lincoln Journal Star, 8 Jul. 1944, pg. 1. Newspapers.com

“British War Relief Society Now in New Headquarters.” The Lincoln Star, 21 Feb. 1943, p. 16. Newspapers.com

Block, Melissa. “Yes, Women Could Vote After The 19th Amendment – But Not All Women. Or Men.” NPR, NPR, 26 Aug. 2020, www.npr.org/2020/08/26/904730251/yes-women-could-vote-after-the-19th-amendment-but-not-all-women-or-men.

Buildings and Grounds, Records, (RG-52-02-00). Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

Häberlen, Joachim C. “Scope for Agency and Political Options. The German Working-Class Movement and the Rise of Nazism.” Politics, religion & ideology 14.3 (2013): 377–394. Web

“Head of Elocution Department Back: Finished Suffrage Tour Throughout State-Confident that People are for Cause”. The Daily Nebraskan [Lincoln], 18 Sept. 1914, p. 1. Nebraska Newspapers

Hill, Paula. “Unlearning History: The Women’s Suffrage Movement.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 20 Aug. 2020, www.pbs.org/education/blog/unlearning-history-the-womens-suffrage-movement.

J. Patras, WWI Photographs (MS 0283). Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries

Jensen, Kimberly, and Christopher Mcknight Nichols. “The War to End War One Hundred Years Later: A First World War Roundtable.” Oregon historical quarterly 118.2 (2017): 234–251. Web

Karrin Vasby Anderson (2020) The centennial of (white) woman suffrage: Gender and democratic engagement at the intersections, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 106:3, 225-233, DOI: 10.1080/00335630.2020.1786638

“League of Women Voters: Celebrates Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of Founding.” The Lincoln Star, 16 Feb. 1945, p. 9. Newspapers.com

“Lincoln as a School Town: Educational Advantages of Nebraska’s Capital.” The Nebraska State Journal [Lincoln], 30 Dec. 1906, p. 33. Newspapers.com

“”Love of the Home One of the Great Fruits of the War”, Writes Miss Alice Howell from Advanced Hospital Base Just Before Armistice.” The Lincoln Star, 15 Dec. 1918, p. 19. Newspapers.com

“Miss Howell Has Returned.” The Daily Nebraskan [Lincoln], 31 Oct. 1919, p. 4. Nebraska Newspapers

“Miss Howell’s Recital.” The Nebraska State Journal [Lincoln], 4 Feb. 1901, p. 8. Newspapers.com

“Miss Howell Returns With Enviable Overseas Record: Professor of Dramatic Art Saw Fourteen Months in France as Canteen Worker.” The Daily Nebraskan [Lincoln], 31 Oct. 1919, p. 1. Nebraska Newspapers

“Miss Howell Rites.” The Lincoln Star, 10 Jul. 1944, pg. 2. Newspapers.com

“Miss Howell Rites Tuesday: Well Known U. of N. Teacher Kept Spoken Drama Alive in Lincoln.” The Lincoln Star, 10 Jul. 1944, pg. 1. Newspapers.com

Mossholder, Robert. “Alice Howell Recalls War Days In France With Walt Disney As Her Chauffeur.” The Nebraska State Journal [Lincoln], 13 May 1934, p. 27. Newspapers.com

“Nebraska Notes: The New Temple At Lincoln.” The Gibbon Reporter, 1 Nov. 1906, p. 7. Newspapers.com

Nebraska Repertory Theatre, Theatre Arts Department Records, RG-12-36-02. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

Nebraska Repertory Theater, Records, RG-57-06-00. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

“Overseas Women Recall Torpedoes Hospitals Doughnuts and Doughboys.” The Nebraska State Journal [Lincoln], 11 Dec, 1927, pg. 42. Newspapers.com

“Pies, Doughnuts and Cakes Keeps One Busy: So Writes Professor Alice Howell from Canteen Work in France.” The Daily Nebraskan [Lincoln], 26 Mar. 1919, p. 1. Nebraska Newspapers

Radke-Moss, Andrea G. Bright Epoch: Women and Coeducation in the American West. University of Nebraska Press, 2008. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1dgn512. Accessed 6 July 2021.

Robinson, Karen R. “Comparing the Spanish Flu and COVID?19 Pandemics: Lessons to Carry Forward.” Nursing forum (Hillsdale) 56.2 (2021): 350–357. Web.

“$66,667 from Mr. Rockefeller”. The New York Times, 13 Apr. 1903, p. 5. Newspapers.com

“Spanish Flu Makes Appearance At University: Authorities May Have to Adopt Severe Preventative Measures.” The Daily Nebraskan [Lincoln], 1 Oct. 1918, p. 1. Nebraska Newspapers

Standish, Jennifer et al. “In Place to Make Change: NC2020 and the Commemoration of Women’s Suffrage.” Southern cultures 26.3 (2020): 156–171. Web.

Theatre Arts Department, College of Arts and Sciences Records, RG-12-36-00. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

Theatre, Fine and Performing Arts Records, RG-57-03-00. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

Theatre Scrapbooks, Theatre Records, RG-57-03-01. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Oct 30, 1999; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. C14

World War I, Publications & Artifacts, (MS 0043). Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries

Credits

This exhibition was created as part of the Schmidt Family Library Internship 2021 by graphic designer, UNL senior Amanda Rigsby. Special thanks to Alan Nielsen, who started a biography on Miss Howell in the 1970’s and procured much of the sought-after information. Another thanks to Christopher Shonka and the JCSTF archives team, for the best three years and a new found love.